The Wire Recorder

Recover audio treasures from the 1940s

Ever wonder what came before tape recorders?

We’ve been digitizing audio for years, using the venerable Otari reel-to-reel, rackmount cassette, microcassette transcriber, DAT machine, miniDisc, and vinyl. But a marvelous contraption came our way in December:

This is a Webster 180 from the late forties, along with a box of 15-30 minute recordings. It works perfectly, and has been added to our menu of media types. (There is a good article about wire recording over on Wikipedia, if this ancient technology is unfamiliar.)

The first question, once I started playing the wires and marveling at the clear sound from long-ago, was how to integrate it with my audio crosspoint switching system. I was not sure how much to trust ground isolation in a machine made 75 years ago, complete with non-polarized power plug… so for initial testing I just lay my phone on top above the speaker and used a recorder app.

The results were amazingly good — here are some school children in Falmouth, Massachusetts, circa 1949…

The mechanics of the machine are interesting. The head, that brown cylindrical object, is passing wire at 24 inches per second. In order to have it lay smoothly on the reels, it cycles up and down, easily visible while rewinding:

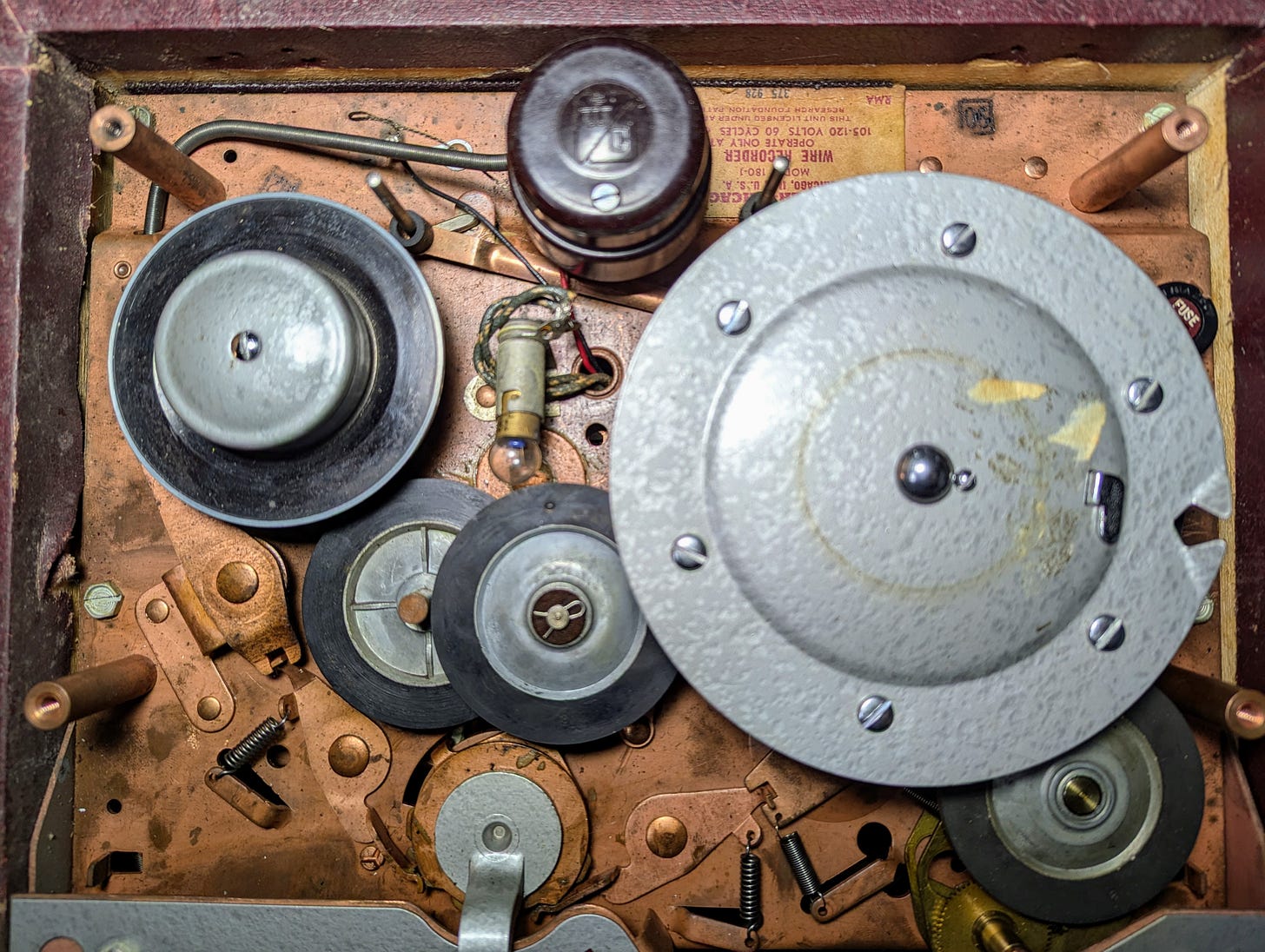

Of course, I couldn’t resist opening it up to poke around while putting some Athan cleaning solution on those old rubber drive wheels. They don’t make ‘em like they used to… this thing is built like the proverbial tank.

The wire is very fine at .004 to .006 in (0.10 to 0.15 mm), and if it gets out of control, you have a mess on your hands. There is a smooth leader line that is captured by the take-up reel, and the source reel has a clever arrangement with a loop that triggers a tension sensor, stopping the transport immediately so you don’t have to re-thread.

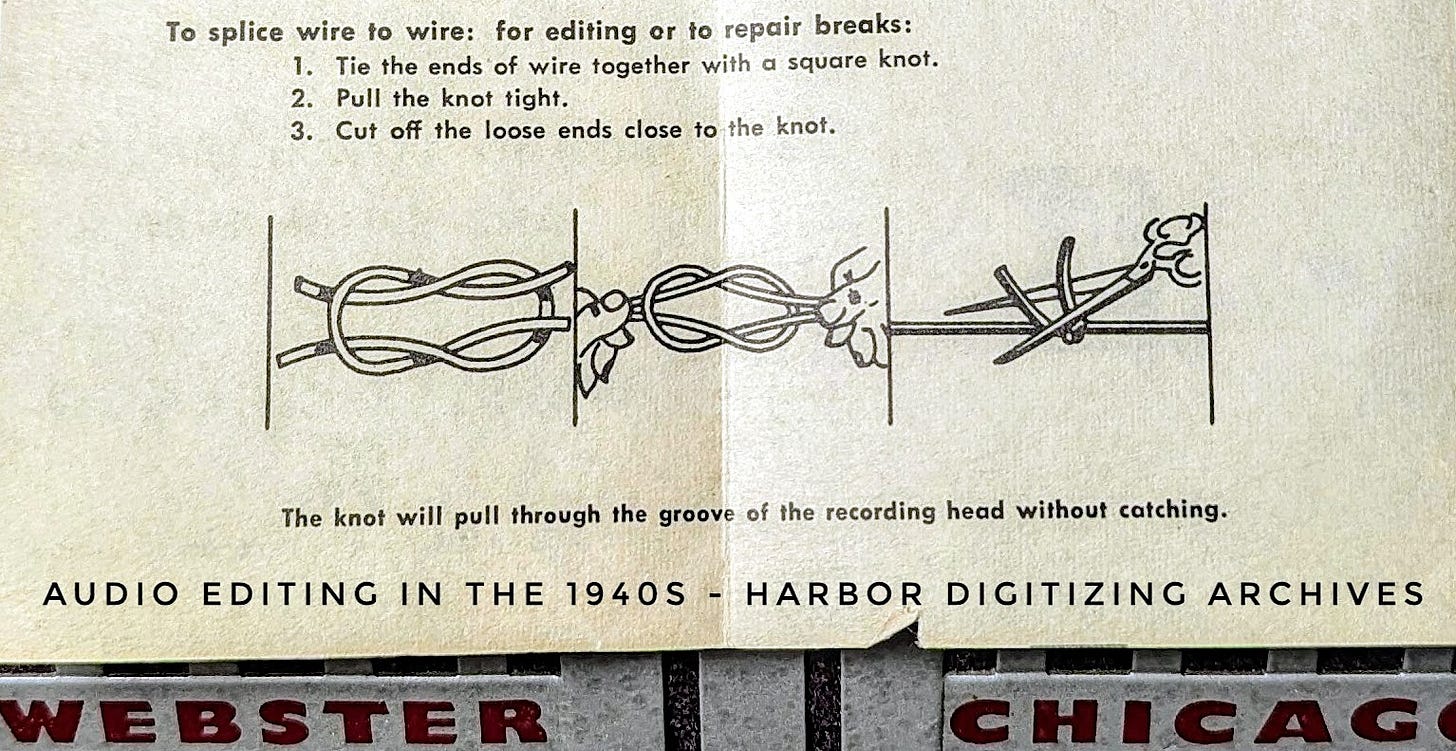

Splicing or editing is a whole different process with this technology, compared to tape. I actually had to do this, after a reel got away from me and had to be untangled, and it is non-trivial. I find this image in the included instruction booklet delightful:

But for digitizing the miles of wire that I expect to arrive after we add this to our <cough>website</cough>, I wanted something more reliable than laying the phone on top of the unit. While listening to these, I captured NAS fan noise, phone notifications, plaintive Isabelle dinner-request mews, and snippets of ham radio repeater traffic. Rather than set up an isolation transformer to avoid potential ground loops, I decided to use my battery-operated Zoom field recorder, connected by a cable.

My ancient parts inventory from childhood naturally included the requisite 2-pin Jones plug, and if you ever want to replicate this, the larger terminal on the round output connector is ground, and the smaller one is signal. The 3-position output switch must be in position 3, which sends line-level audio to the jack. (Position 1 connects amplifier output to the speaker, and position 2 routes that to the jack… so careful to select 3 to prevent overwhelming a line-level input.)

My machine still has a 60 Hz hum, regardless of line cord orientation, almost certainly caused by ancient bad filter capacitors that I should replace immediately. That's on the to-do list, since EQ notching with Audacity significantly affects voice quality. Still, it is pretty fun — here is a fellow reading some tales of Coast Guard exploits involving rum-runners:

This is that segment from the 15-minute reel, if you want to feast your ears on the speaking style of the time (recorded via the lashup in the photo… using Audacity noise reduction to reduce hiss and hum):

Incidentally, should you decide to record on one of these machines (from a source other than the original art deco microphone), the 3-terminal Jones plug on the left of the front panel is the way to do it. That rectangular plug is ground on top, high impedance (4.7MΩ) microphone level in the middle, and line level input at the bottom.

My experience with this so far has been delightful, and I’m thrilled to add the Webster to our suite of audio tools in the digitizing lab. I’ve been very conscious lately of the vulnerability of the world’s analog archives, and a critical part of that involves restoring and using these arcane contraptions that handle retro media in all its forms.

The topic backlog here at the Digitizing Report is epic, and much of it attempts to help build a library of techniques and resources to help keep these processes going as long as there are analog recordings that need to be captured. Many decades from now, people will still be finding great-grandfather’s old stash of tapes, yet the people who have grown up with this technology will be long-gone, their labs mined for eBay or carted to the dump. It is up to us to get their extensive knowledge into useful collections that will outlive individual websites. Spare parts will also become extremely precious, as will un-scanned documentation binders and other reference material. Labs like mine are fragile time machines that break when we do.

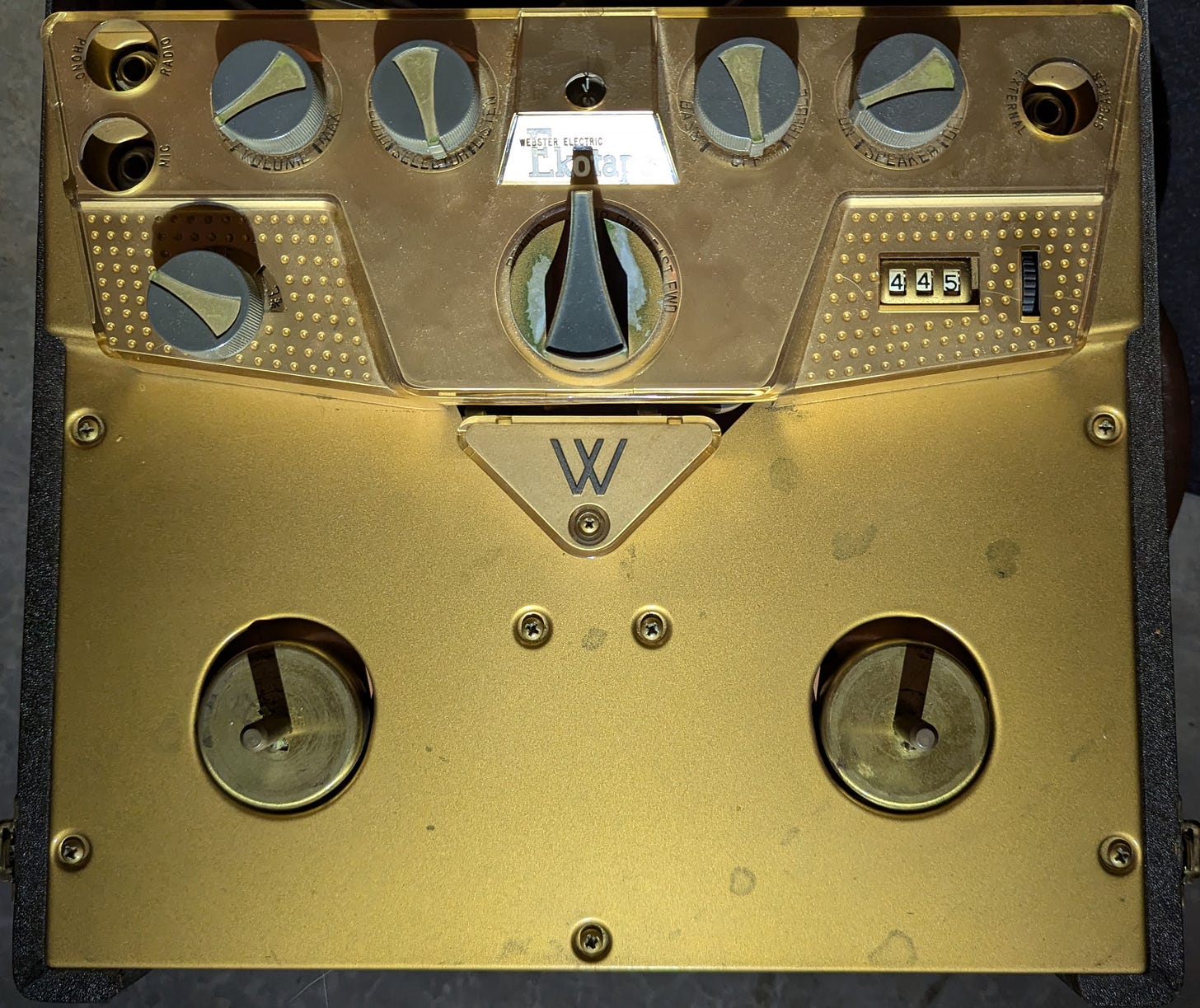

Speaking of audio arcana, the Webster company in Chicago that made the Model 180 was also a producer of those newfangled tape recorders. We have one of their early models from the fifties, an elegant design statement from 75 years ago:

Much of my overload of late has involved both using and refining the 48-foot ostensibly mobile digitizing lab, a distant descendant of my computerized bicycles back in the 1980s when I was wandering the US as the first “digital nomad” (though back then, my term was high-tech nomad, or technomad). I mention this because I recently started another Substack publication — subscriptions are free, and its home page with archives can be found at Nomadic Research Labs. The introduction is here, complete with a voice-over recorded on much more modern tools:

Cheers from the lab, where I’m working on a backlog of 35mm slides while experimenting with parallel image-capture workflows. More on that in a future issue of the Digitizing Report!

Reader comment about interfacing

This is an amazing idea — I need to try it, with my dbx286 rackmount channel strip mounted right next to the table where I set up the wire machine. Thanks to Gary Shell for this reply:

I saw your story about the wire recorder today. I have an identical one from my grandfather.

I too, had trepidation about connecting it to other gear. I owned a recording studio in Cincinnati and had access to a lot of stuff that I could use to clean up recordings, but the thought of direct connecting the output of that to my console gave me the willies.

I started poking around with an oscilloscope and looked at the signal coming directly off head. To my surprise, it looked a lot like that coming from a dynamic mic. So I disconnected the head from the recorder's electronics and connected it to the input of a mic preamp. Voila! I had beautiful clear sound. No worries about spurious AC voltage issues. No EQ was needed. It seems that the was no pre-emphasis in getting the signal to the wire, so there was no need for reversing that when playing back.

I transferred hours of recordings my grandfather had made, edited the stuff into a CD that I gave to family members that Christmas. The tears flowed when we got to hear my grandmother play piano and my grandfather singing with her.